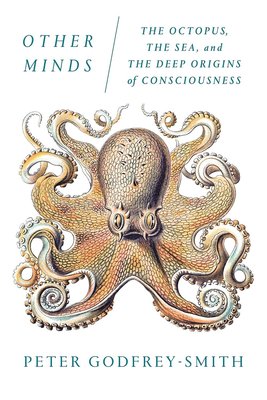

Philosopher Peter Godfrey-Smith dons a wet suit and journeys into the depths of consciousness in Other Minds Although mammals and birds are widely regarded as the smartest creatures on earth, it has lately become clear that a very distant branch of the tree of life has also sprouted higher intelligence: the cephalopods, consisting of the squid, the cuttlefish, and above all the octopus. In captivity, octopuses have been known to identify individual human keepers, raid neighboring tanks for food, turn off lightbulbs by spouting jets of water, plug drains, and make daring escapes. How is it that a creature with such gifts evolved through an evolutionary lineage so radically distant from our own? What does it mean that evolution built minds not once but at least twice? The octopus is the closest we will come to meeting an intelligent alien. What can we learn from the encounter? In Other Minds , Peter Godfrey-Smith, a distinguished philosopher of science and a skilled scuba diver, tells a bold new story of how subjective experience crept into being―how nature became aware of itself. As Godfrey-Smith stresses, it is a story that largely occurs in the ocean, where animals first appeared. Tracking the mind’s fitful development, Godfrey-Smith shows how unruly clumps of seaborne cells began living together and became capable of sensing, acting, and signaling. As these primitive organisms became more entangled with others, they grew more complicated. The first nervous systems evolved, probably in ancient relatives of jellyfish; later on, the cephalopods, which began as inconspicuous mollusks, abandoned their shells and rose above the ocean floor, searching for prey and acquiring the greater intelligence needed to do so. Taking an independent route, mammals and birds later began their own evolutionary journeys. But what kind of intelligence do cephalopods possess? Drawing on the latest scientific research and his own scuba-diving adventures, Godfrey-Smith probes the many mysteries that surround the lineage. How did the octopus, a solitary creature with little social life, become so smart? What is it like to have eight tentacles that are so packed with neurons that they virtually “think for themselves”? What happens when some octopuses abandon their hermit-like ways and congregate, as they do in a unique location off the coast of Australia? By tracing the question of inner life back to its roots and comparing human beings with our most remarkable animal relatives, Godfrey-Smith casts crucial new light on the octopus mind―and on our own.